This article was first published in September 2019 and was last updated in June 2020.

First-time visitors to the Land of Morning Calm are usually overwhelmed with the choice of dining options and admire the rich cultural heritage that comes along with Korean food.

Most people know about the ubiquitous kimchi, but when they arrive, they learn that there are actually over 100 types of the fermented food from spicy to white, using cabbage or cucumber.

The list below will go through all the usual suspects in Korean cuisine, from bulgogi and samgyeopsal to fried chicken and tteokbokki. But it will also explain some of the lesser known Korean dishes (to foreigners at least) as well as a little bit of history and etiquette at the table.

So get your palate ready for a degustation adventure in one of the most unique and diverse menus on the planet. Here is your list of all the best (and worst) Korean food.

The history of Korean food

Before becoming South Korea, the country went through many changes. Traveling back to around 57 BC, the most significant period in Korea’s recent history began with what is known as the Three Kingdoms.

The Three Kingdoms, from 57 BCE to 668CE, was a time of rapid cultural evolution, and with it came the evolution Korean food. Goguryeo (37 BCE – 668 CE) was in the north, Baekje (18 BCE – 660 CE) was located in the southwestern peninsula and Silla (57 BCE – 935 CE) was situated in the southeastern peninsula.

Because of their geographical location, each kingdom had separate cultural practices and foods. Baekje, for example, was known for its cold and fermented foods like kimchi.

The next significant period in Korea’s culinary history was the Goryeo period (918-1392). After the Mongols invaded in the 13th century, many of the favorites of today were established such as mandu (dumplings), noodles, grilled meats and the introduction of seasonings like black pepper.

Levantine distillation was also brought by the Mongols during the Goryo Dynasty, and along with this came the introduction of alcohol. Although the milky makgeolli was already in consumption since Goguryeo, the clear soju (similar to the Japanese sake) was invented then.

Many agricultural innovations were implemented in the Joseon period (1392-1897). Books on agriculture and farming techniques were even published from 1429 under then ruler King Sejong who also created the new Korean alphabet called hangul (originally “Hunmin chong-um” or “the correct sounds for the instruction of the people”).

Korea then started looking outside its own country to expand its knowledge and ventured into trade with China, Japan, Europe, and the Philippines (which was receiving foods from the Americas via the Spanish trading routes).

Along with this venture came foods such as corn, sweet potatoes, chili peppers, tomatoes, peanuts, and squash.

Throughout the 19th century, the government also introduced reduced taxes on the peasantry, which meant, along with complex irrigation systems, they could expand growth and sell their crops. Markets started to appear and were centers for trade and entertainment.

After opening its doors to the Western world after trade agreements in the 1860s, Western missionaries and travelers brought their own foods and ingredients from countries like the United States, Britain, France.

During Japanese colonization (1910-1945), Korea was used as a sort of food support system for Japan where larger yields of grains, particularly rice, were created.

Food was scarce for the lower class at this time, but the middle and upper classes enjoyed all the foods that Korea, Japan and the Western world had to offer.

The tumultuous Korean War (1950–1953) separated North and South and food provisions were limited. This led to the use of inexpensive items in stews and meals such as budae jjigae (army stew) were created.

After the 1960s, under President Park Chung-hee’s rule, industrialization started to boom, and along with it the introduction of modern farming techniques and pesticides.

Instant and processed food began to pop up in the 1970s and meats of all kinds, steadily increased in the average Korean’s diet – from 3.6kg in 1961 (per-capita consumption) to 40kg in 1997. And of course, bulgogi restaurants started to rapidly appear.

Coffee culture is massive in Korea today and talking about Korean food and drinks should always include coffee. Coffee, the most popular non-alcoholic beverage in Korea was also introduced in the early 20th century as the elite were interested in Western culture and foods.

“Dabangs” or cafes started popping up in Seoul from 1927 and were popular meeting places. They were originally only open to the elite class and royals. In the 1960s dabangs opened to the middle class and were popular among college students who could gather in freedom and talk about politics.

Starbucks was introduced in 1999 in Sinchon, Seoul, and the dabangs of old were taken over by the newer take-out and self-service system of the Western cafe. In 2015, there were an estimated 49,600 coffee shops in South Korea, with 17,000 in Seoul alone. There seems to be a coffee shop on every corner, sometimes even 3 in one corner if that’s even possible.

Korean dining etiquette and differences

Before getting into the various and delicious Korean foods, it’s good to know what the etiquette is so that you don’t have any cultural faux pas.

Unlike the individualistic eating style of the West, Korean dining is communal and hierarchical and is a glimpse into the Confusionist past of the country.

Banchan (side dishes) & Anju (meals served with alcohol)

The first difference that mostly all foreigners notice when dining in Korea are the multitude of side dishes (banchan) that arrive and never cease to end. The main dish usually comes with several banchan which are completely free.

Historians believe that banchan is a result of Buddhist influence during the Three Kingdoms period. With the rise of Buddhism and ban on meat, vegetable-based dishes rose in prominence and became the centre of any meal.

Even though the Mongol invasions saw an end to the ban of meat-based dishes, the vegetable banchan dishes were already ingrained into Korean dining culture.

A typical Korean table setting usually consists of bap (밥, cooked rice), guk or tang (soup), gochujang (chili paste) or ganjang (soy sauce), jjigae (stew), and kimchi.

The banchan are placed in the centre of the table, surrounding the main dish, and are meant to be shared. Cooked rice is served separately in small bowls.

The table setting of banchan is also known as bansang. Depending on the dishes served the table is called 3 cheop (삼첩, samcheop), 5 cheop (오첩, oecheop), 7 cheop (칠첩, chilcheop), 9 cheop (구첩, gucheop), 12 cheop (십이첩, shipilcheop) bansang. The more formal the meal, the more banchan.

Banchan comes in several forms from the various kimchi to namul (나물, steamed, marinated, or stir-fried vegetables), bokkeum (볶음, stir-fried with sauce), jorim (조림, simmered in a seasoned broth), jjim (찜, steamed), jeon (전, pan-fried, pancake-like dishes) and others.

You can even ask for more if you need, but don’t get too greedy. You are also expected to finish your dish dishes if you ask for seconds, lest you want evil looks from the owner.

Some restaurants even have self-help side dish stations where you can collect your own banchan.

Anju is a term used to describe the food that is consumed along with alcohol. When entering a Hof or bar you will notice that you can’t just get a drink, but will need to order food as well. This is even after you have had a full meal.

Obey the hierarchy

Similar to almost anywhere in the world, elders are number 1 at the table and all eating and drinking revolves around the oldest person. You should wait for the oldest person to sit first and to lift their utensils first.

The meal then revolves around the oldest member of the group, refilling drinks, eating at their pace and deciding what to order.

Choosing what to eat

In Western cultures the group will usually discuss what they want to eat together and come up with an ultimatum or meet halfway.

While it is lessening up in Korean culture, the group will usually eat what the oldest person wants to eat without complaining. That person is also expected to pay for the meal.

Korean table manners

Number one: Do not blow your nose at the table. If the spicy foods do make your nose run, excuse yourself and blow it in the bathroom or outside. Not only is it considered rude and dirty, it is also embarrassing for the people you are eating with as the rest of the diners will glare at you.

Before you start eating and after you’re done, say Jalmukesumneda (I will eat well) or Jalmokosumneda (I ate well). The rest of the diners will echo your well wishes.

Water is usually self service or a bottle will be brought to the table with small glasses. It is very good manners to fill everyone’s glass with some water. Don’t expect a thank you in words, but everyone will notice and be grateful.

When pouring any drink for someone senior, place your other hand lightly under your pouring hand or your opposite elbow. If they offer you a drink or food, lift your plate or glass toward them with two hands. It is considered rude and ungrateful not to accept it.

Eat at the pace of the oldest member without rushing or lingering. It’s not a competition and enjoying your meal at the same speed allows for an enjoyable meal.

Utensils should be used one at a time, don’t hold your chopsticks in one hand and spoon in the other. Place the one you are not using down on the table and not sticking into the rice. Your rice bowl should also be set on the table without being lifted, unless you are eating with a friend.

As most of the Korean food is shared, take as much as you need and leave enough for the rest of the people at the table. There will always be a piece that no one will touch, otherwise they seem greedy. If you are familiar with your dining guests, take the last piece and place it on someone else’s plate instead of your own.

Self service

Most restaurants and eateries will have self-service water that you can fill up at anytime. You don’t even need to ask. If you do ask for mul (water) you may get the answer “self” (which sounds more like “selu pf”).

Also note that you are expected to return your tray and throw away any leftovers when eating at a coffee shop or food court.

Tip: If you are sitting at a restaurant and can’t find your cutlery anywhere, sometimes they are hidden in a draw under the table, along with napkins. Or in a small wooden or plastic box with a lid.

After the meal

The meal usually doesn’t end at the restaurant and it’s not uncommon to go with your group to several other destinations including a Hof or Bar (where food must be ordered with your drinks), cafe, dessert place and of course noraebang (karaoke).

How to categorise the types of Korean food

With so much variety, it’s difficult to categorise all the various different kinds of Korean foods. We’ve had a long hard think about it and have come up with the following categories.

There is some overlap, for example, bulgogi is a meat-based and a steamed dish, but the list will give you a better idea of the different styles of Korean dishes.

- Meat-based

- Fish-based

- Vegetable-based

- Soups & stews including guk, tang, jjigae & jeongol

- Steamed or boiled dishes

- Raw dishes

- Grain dishes

- Noodles or guksu

- Banchan and anju

The difference between Guk, Tang, Jjigae and Jeongol

In English, there are a few words used for soups depending on the consistency and methods of cooking, for example, stew, broth, bouillabaisse and borscht. This is the same in South Korea.

Guk is the word used for soup, meaning that it is usually not shared and served in individual portions along with rice. It is more of a clear consistency.

Jjigae is a thicker, heartier soup where the main ingredient is not the broth, but rather the solid ingredients like vegetables, tofu, fish or meat. Jjigae is meant to be shared.

Tang (pronounced tongue) is similar to guk, but the broth is cooked for longer periods of time. Here, it is all about the broth and can be served individually or to be shared. Additional seasoning or condiments are generally added after being served, unlike guk.

Jeongol is a hot pot meal that is cooked at the table. Broth is poured over raw ingredients continually during the meal. Shabu shabu is jeongol’s cousin, where the ingredients are put into the broth and cooked at the table rather than the broth being added. This is also a shared dish with Japanese cuisine.

Most popular Korean foods

Now that you understand the different types of dishes, let’s get into the most popular Korean foods, loved both by the local and international communities.

Bibimbap (mixed rice)

Bibimbap is probably the most accessible Korean food on the list. Literally translated to “mixed rice”, it is a simple, yet surprisingly satisfying dish both for its taste and for the tummy.

So, what’s in this dish that makes it so appetising?

It’s a bowl with glutinous rice at the bottom and covered in a selection of nutritious and healthy goodies that range from restaurant to restaurant. The usual suspects include sliced beef, sautéed vegetables (namul), a few sauces (soy, doenjang and gochujang), with an egg cracked on top.

Once served, take your elongated spoon and start folding the ingredients together. Add in more of any sauce you desire for taste. The ketchup bottle will be filled with gochujang (chilli paste), many Westerners mistake this and have quite the surprise after pouring it.

What makes this dish different from other international variants, say poke bowls, is both the sauces used and the namul. The namul, or sautéed seasoned vegetables, will include some authentically Korean items from daikon radish to bracken fern stems (gosari) to soybean sprouts to roots and stems of all kinds.

The main sauced used is gochujang which is a fairly spicy chili paste, usually with salt, fermented soybeans, glutinous rice powder, with sugar and garlic added. It’s more like Thailand’s sriracha or Malaysian sambal oelek than the more unpalatable fiery chilli found in India or Bangladesh.

The best bibimbap is served in hot stone bowls (dolsot) and is known as dolsot bibimbap. The stoneware allows the meal to be further cooked after being served and the rice usually ends up sticking to the sides and becoming crunchy, this makes it extra satisfying.

When you finish the meal, the waiter will come with some hot water and pour it in your boil, which you can drink as a hot rice tea.

Bulgogi (marinated beef)

Bulgogi is simply a tender thinly sliced marinated beef dish using a soy sauce base that usually comes with a side of rice. You can eat it with a spoon or put a piece of lettuce in your hand and wrap it up before eating.

The meat used is usually ribeye due to its tenderness and fat content, yet some establishments will use sirloin and brisket. The marinades used will most likely consist of soy sauce, sugar, garlic, green onion, sesame oil and pear.

Why pear?

Pear contains an enzyme called calpain, this is used to tenderize the meat while adding a juicy sweetness.

The dish apparently has its origins in the Goguryeo period with a dish called maekjeok, a kabob-like skewer of meat. This evolved into seoryamyeok where the marinated beef was soaked in cold water. And then neobiani, a meal of thinly-sliced, marinated and charbroiled beef that was usually enjoyed by the Royals of the time.

The commercialization of beef in the 1920s led to the introduction of bulgogi to the masses, although it did wane during Japanese colonial rule as shortages in beef grew. In the 1990s bulgogi once again became of national favorite.

As Koreans immigrated to the US, they brought along home-made staples, the most popular being kimchi, bibimbap and bulgogi. Bulgogi has evolved into two styles, one is more of a broth while the other is grilled over a hot skillet. Both are delicious, so try each one and see which is your favorite.

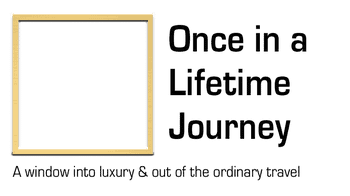

Samgyeopsal (three-layered pork)

Samgyeopsal (literally “three-layered flesh” in this case pork meat) is one of the most popular Korean meals.

When people talk about Korean BBQ, they are usually referring to either samgyeopsal or a beef variant like galmaegisal (“seagull flesh”, which is marinated beef that is in the shape of a seagull or chevron).

The strips of delicious pork belly are self-grilled over a hot gridiron and eaten directly off the centre of the table. The meat can either be cooked over a portable gas burner or with the use of charcoal for a smokier taste.

While the samgyeopsal is cooking, you can also throw on some garlic, mushrooms and kimchi. The meal comes with unlimited sangchu (lettuce) where you need to ask for more if needed, coarse salt and gireum-jang (sesame oil, salt, and black pepper) for dipping, and various sauces and of course banchan like kkaennip (perilla leaves), ssammu (pickled radish paper), and the delicious ssamjang (mix of chili paste and soy bean paste).

Koreans love showing foreigners the correct way of eating samgyeopsal, but if you want to impress them, here’s how to eat samgyeopsal.

Pro tip: After consistently turning the meat, it must be cut along the width to make smaller pieces. When these are brownish, take a piece with your chopsticks in one hand and sangchu in the other and place the meat into the sangchu, dipping it in the salt and gireum-jang before.

Then take some ssamjang, garlic and mushroom and place it altogether. Fold the lettuce over the meat and other ingredients and fold again. This ball of goodness is usually eaten in one go. Watch out for bones, which you will elegantly spit out into a napkin.

The best alcohol for samgyeopsal is clear soju which will wash away any fatty residue. The meal also usually comes with a broth, mostly doenjang-jiggae or soontubu-jiggae. Remember you can ask for a replacement grill if yours becomes too charred with burnt meat.

The meal is communal and a very good setting to familiarise yourself with a new colleague or friend. The alcohol, sharing of food and jovial atmosphere makes for the perfect setting to let your guard down and have a laugh outside of the stringent working environment.

If you really want the best tasting cuts, you will need to travel to Jeju Island. Here the meat is called ogyeopsal (five-layered meat) and is used from the island’s black pigs. Don’t worry when the meat comes with some of the hairs attached, this is to show the customer its authenticity.

Samgyeopsal is also used in various other dishes from suyuk (boiled and cut beef or pork on a bed of greens over broth) and kimchi-jiggae being the most prominent.

Kimchi jjigae (kimchi stew)

Probably one of the most common foods in Korea, kimchi jjigae is pretty self explanatory. It is a stew made with kimchi and other ingredients like scallions, tofu and pork or seafood.

One of the major things to know about kimchi jjigae is the age of the kimchi itself. Older, and therefore more “ripe” kimchi, has more health benefits as it contains higher amounts of “good” bacteria (similar to yogurt).

Older kimchi also allows for a deeper and more robust taste. So first timers should go with newer kimchi. And watch out when the dish arrives, it usually comes in a piping hot stone bowl. And of course, it is usually very spicy and comes with banchan and a bowl of rice.

Doenjang-jjigae (soybean stew)

Doenjang-jjigae is a stew made from the soybean paste doenjang and also includes tofu, zucchini and other ingredients that will vary depending on who is making it.

Doenjang is close to the Japanese miso, as it is made from fermented soybeans, but has a punchier and fuller taste.

Doenjang-jjigae is said to act as an energy booster and has health benefits such as containing lactobacillus that the Korea Food Research Institute says helps to improve the immune system as well as the inner organs.

Before, doenjang-jjigae can range from mild to extremely spicy, so if you cannot handle fiery foods, make sure it is the milder type. You can try asking “Mae-wah-yo? (매워요?)” which means “Is it spicy?”, but chances are they will say no even if it is as their tolerance is different.

Vegetarians should also watch out as even though this seems like a dish only made using vegetables and tofu, the broth can occasionally contain anchovies (gang doenjang jjigae, 강된장찌개) or even, in rare circumstances, meat of some kind.

Sundubu jjigae (soft tofu stew)

If you go shopping in South Korea, you’ll notice that there are so many different kinds of tofu from soft to hard, used for boiling or frying. Sundubu-jjigae means soft tofu stew, and when I say soft I mean silky soft.

The tofu hasn’t been strained or pressed and is usually freshly curdled. So you know it will melt in your mouth.

A variety of vegetables are also thrown in from mushrooms and onion, and depending on where you eat, there are also seafood and meat varieties, and sometimes an egg is broken on top of the piping hot dish.

Similar to doenjang-jjigae, it is also made using gochujang or gochu karu (chilli powder) and can be extremely spicy. Sundubu-jjigae is a popular dish for vegetarians when it’s in its purest form. But do watch out as the broth may be made using anchovies.

Budae jjigae (army base stew)

This spicy broth is literally translated to “army base stew” but is also called sausage stew. It was a Korean food made shortly after the Korean war with smuggled US surplus processed meats like spam, sausage, ham and baked beans. Kimchi and gochujang was also added for the Korean palate.

It’s the perfect fusion between East and West ingredients and many Westerners enjoy it. Ramen can also be added to the stew, as well as cheese and tteok.

There is even a budae jjigae street in Uijeongbu, just north of the Bukhansan mountain range in Gyeonggi Province, where the dish was created.

Interesting fact on South Korea: Then president of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson loved the dish so much that it was nicknamed Jonseun-tang or “Johnson soup”.

Kongbiji jjigae (ground soybean stew)

While this isn’t one of the most popular dishes in Korea, it is one of my personal favorite (Koreans say I have an older palate). It’s made from the pulp of soaked soybeans which is usually the leftover pulp from making tofu.

The process of grinding the soybeans into a pulp, pureeing and then filtering them through a sack results in a creamy stew that has a unique texture – at once soft and grainy. Add some kimchi to enhance the flavor.

Dak galbi (spicy stir-fried chicken)

Strangely, the word for chicken in Korean is “dak”. The word for duck is “ori”. It’s a bit confusing at first, but you get the hang of it after a while. Dak galbi is literally translated to “chicken ribs”, but the meal is in fact not that.

Dak galbi is spicy stir-fried chicken where the meat is diced and marinated in a gochujang-based sauce. It usually comes with sweet potatoes, cabbage, perilla leaves, scallions, tteok (rice cake), and other ingredients depending on where you go.

You usually get ssam which is a word that means “to wrap” on the side like lettuce or other green leaves.

The dish was originally created as a cheaper alternative to other gui (grilled) chicken dishes. As it could be prepared in large amounts at an inexpensive cost, it became popular with army soldiers and university students.

The best place to eat dak galbi is definitely Chuncheon where it originated. There’s even an annual dak galbi festival and a dak galbi alley!

If you love chicken and spicy food, and I really mean fiery, then try jjim dak. This super hot dish from Andong is a great alternative if you’re looking for something similar but with more of a broth base. It also usually comes with extra chewy noodles. You can also ask for the less spicy soy sauce based version.

Miyeok guk (seaweed soup)

Although miyeok guk is usually a side dish, I have included it here as I enjoy it as a meal on its own, especially for breakfast. The name translates to seaweed soup and it is one of the healthiest Korean foods on this list.

Seaweed is super healthy, it is a great source of vitamin K, and there are hundreds of different varieties (my favorite is the super soft maesaengi which is like soft angel hairs floating in a bowl).

Miyeok guk is typically made with other seafood products like mussels, anchovies, clams or oysters. It also has a soy sauce base and beef can also be added.

Pro tip: miyeok guk is better the day after it has been cooked as it becomes thicker and all the ingredients really pop. Try cooking it at home and then eating it for brekkies the next day, it’s delicious.

Several interesting cultural anecdotes follow this delicious slippery seaweed soup. The first is that miyeok guk is also known as birthday soup and is always prepared specially for anyone’s birthday. It is said that during the Goryeo dynasty, people saw whales eating seaweed after giving birth and so the tradition began.

Mothers are known to eat this soup directly after giving birth as it is said to produce healthier milk for breastfeeding, along with helping to nourish the baby. It contains calcium, iodine, fiber, omega acids, vitamin B1 & B3.

The third anecdote is more of a superstition. As the SATs are so important in Korea, students will try anything to gain the best results. Mothers often don’t feed their offspring miyeok guk before an exam as they say the slipperiness of the seaweed will make the information slip out of the brain.

Samgyetang (ginseng chicken soup)

South Korea is known worldwide for its super high quality ginseng. Combine this super healthy root with a full baby chicken and put it in a clear broth and you have the amazingly robust samgyetang.

The chicken is filled with other ingredients that are beneficial for your body like garlic, rice and jujube. It’s one of the most popular Korean foods for a hot summer day as it is said to promote health even more.

Why?

The explanation is quite scientific but easy enough to understand. While our external body temperature increases on hot days, our internal organs do not. Eating this hot dish helps to boost our internal body temperature which makes us sweat more, and in turn, cools us down.

Samgyetang is mostly enjoyed on the three hottest days of the year known collectively in Korea as Sambok (between July and August, “bok” roughly translates to “blessing” and “sam” is “three”) and further divided into Chobok, Jungbok and Malbok. Each day is generally known as “boknal” (day of blessing for your health). Try it out for yourself and see if you feel energised and those super blisteringly hot days.

Fried Chicken & Chimek (beer & chicken)

No one does fried chicken quite like Korea. Although some say it has its origins in the American style soul food, it differs from its predecessor.

So what’s the secret?

Different from the West, Korean fried chicken in Korea is actually fried twice so it is less oily and the skin is even crunchier. The entire chicken is also coated in a seasoning.

Even though chicken is called “dak” in Korean, the term “BBQ chikin” is usually used when referring to this specific style. A more literal translation would be dak-twigim “chicken fritter”, but no one really uses that.

Pickled radishe or cucumber will usually accompany your chicken (the same when you order a pizza anywhere in the country). There are also usually a large selection of dipping sauces. Some chains have expanded to North America including Mexicana Chicken, Genesis BBQ, Kyochon Chicken and Pelicana Chicken.

The best alcoholic accompaniment to fried chicken is beer or mekju. It is so popular that Koreans often refer to it as chimek or chimak (chicken+mekju) as a meal. Daegu even has its own annual Chimak Festival in July. It is also the most popular thing to nosh on during a baseball game.

Pro tip: For a healthier option, try oven baked chicken at chains like Oppadak (literally “Obeunah Bbajin Dak” or “Chicken placed into the oven”). The meat is as tender and the skin just as crunchy, but as it is not fried it has a cleaner taste.

Mandu & Manduguk (dumplings & dumpling stew)

Dumplings are not a new Korean food to a Western audience, but in Korea it’s the fillings that makes the difference.

Dumplings in Korea are called mandu and they can be steamed (jjin-mandu) like Azeri dushbara, boiled (mul-mandu), pan-fried or deep-fried (gun-mandu) like the Japanese gyoza.

There are many types of mandu in Korea that are filled with all types of ingredients from meat to vegetables to kimchi. A hint for vegetarians is to order so-mandu (소만두) which is meant for Buddhists and therefore has no meat.

Manduguk is a great variation of this dish, which is basically mandu in a clear beef broth. You can also have it with rice cakes or tteok added where it is called tteok manduguk. If you have the same broth without the mandu its called tteokguk and is also delicious.

Seolleongtang & galbitang (ox bone stew & beef short rib stew)

Seolleongtang is a thick broth made with ox bones for taste and usually topped with brisket or other cuts. It is one of the only broths where you add your seasoning after it’s brought to the table. It is great with some ground black pepper.

The best part about this Korean dish, the same with cooking ox bones in any country really, it that it simmers for a long time on a low heat. This brings out a deep flavor from the bones and is super tasty.

A similar dish is made with beef short ribs called galbitang. The dishes are virtually the same except that the main ingredient is different and galbitang is soy-sauce based (so not milky white in appearance), but also cooked for hours.

Jeongol (hot pot)

If you’ve visited other parts of Asia, you’ll know exactly what a hot pot is. For those who haven’t tasted it before, it is a style of cooking where a large bowl with a broth is brought to the table and the diners cook their own ingredients.

These range from meats to fish and various types of vegetables, the most popular being mushroom. In fact, bosot jeongol (mushroom hot pot) it a very popular type of jeongol if you want a break from meat.

Another popular alternative to jeongol is the Japanese adopted shabu shabu. In this dish, the meat is often thinly sliced and sometimes served in a buffet style. After fetching your meat you place it in the large pot at your table.

Kalguksu & Sujebi (knife noodles & pulled dough soup)

While ramen is ubiquitous throughout the country as it is in Japan, and there are more varieties than you can imagine, for a healthier noodle dish, try kalguksu.

Kalguksu is the umbrella term for the various broth that use this special noodle translated as “knife noodles”.

It is handmade using wheat, flour and eggs and then cut using a knife. The same dough can also be ripped or torn to create sujebi (hand-pulled dough soup) for a thicker consistency.

The broth for a traditional kalguksu is made using dried anchovies, shellfish, and kelp that simmer for many hours. Zucchini, scallions and potatoes are cooked separately for a shorter period and added later.

There are so many types of kalguksu, from snail to pumpkin, that we can’t mention them here. But one of our absolute favorites is perilla seed kalguksu (deulkeh kalguksu, 들깨칼국수), if you can find it.

Naengmyeon (cold noodles)

The only cold Korean dish on this list, naengmyeon is a popular summer dish that consists of extremely chewy noodles in a freezing cold sweet soup. Think gazpacho but with a clear texture and noodles.

The dish comes with blocks of ice to keep it cool, along with julienne cucumbers, slices of Korean pear, pickled radish and a boiled egg on top (and sometimes cold boiled beef).

The broth version is called mul naengmyeon, but there is also bibim naengmyeon which is served spicy with gochujang and without the soup.

Another nice cold noodle option to taste is buckwheat soba (memil soba) which is a softer noodle compared to the ultra chewy naengmyeon. It is brown in color, has more of a texture and comes on a slitted bamboo plate instead of in a bowl. It looks more Japanese than Korean and is delicious.

Jajang myeon, tangsuyuk & jjamppong (black bean noodles, sweet and sour deep fried meat & spicy broth)

While these three Korean foods are very different, they are usually served in combination together and are known as “Korean Chinese food”. Although the dishes are not of Chinese origin, they were invented by Chinese immigrants in Korea.

Jajang myeong (black bean noodles) were first introduced in 1905 at a Chinese restaurant called Gonghwachun at the port of Incheon. Jajang does not actually mean black bean but is rather a transliteration of the Chinese word for “fried sauce” – zhájiàng.

The noodles used are thick and chewy to soft and made from wheat flour, salt, baking soda, and water. The sauce is made from chunjang (also known as Tianmian or sweet bean sauce) with soy sauce, oyster sauce, and the addition of meat (mostly pork), seafood, scallions, ginger, and garlic. Vegetables like onions and zucchini are also thrown.

The noodles are then topped with julienne cucumber, boiled or fried egg, and sometimes blanched shrimp or stir-fried bamboo shoot slices. Yellow pickled radish (danmuji), sliced raw onions, and chunjang sauce are served on the side.

The two best accompaniments to jajang myeon are tangsuyuk and jjamppong. Tangsuyuk was first introduced by Chinese Shandong immigrants and had the Chinese characters 糖醋肉 (dangchoyuk) which means sugar, vinegar, meat. It later became tangsuyuk.

The meal is what Westerners usually call sweet and sour and can be made with either beef or pork. The bite-sized golden delicious pieces of meat are coated with a batter of potato starch and double deep fried.

The final Korean-Chinese hybrid that completes the meal is the ultra spicy soup called jjamppong. It is also a Shandong immigrant concoction and is made using seafood or pork with gochugaru (chili powder), onions, garlic, Korean zucchini, carrots, cabbage, squid and mussels.

Hweh (raw fish)

Hweh (also written as “hoe” for some reason) is similar to Japanese sashimi, and is raw filleted fish. This meal is not the usual one or two pieces of tuna or salmon but rather an entire fish presented as a mound on a plate.

There are around 30 different species that you can choose from eel to cod to even octopus. It is a pricey affair and is usually eaten by Koreans when they go on holiday to the seaside or one of the many islands surrounding the peninsular.

The meal comes with various side dishes and dips with the usual ssam (wrap like lettuce) to fold your fresh fish into. After finishing the hweh, the restaurant usually makes a broth from the leftover fish including the head and entrails.

It’s usually quite spicy and similar to chueo-tang which is made from pond loach, doenjang, gochujang and a variety of vegetables.

Other seafood dishes

To anyone that has visited Noryangjin Market in Seoul, Jagalchi Market in Busan, or the coast and islands of South Korea, you’ll know how much Koreans love their seafood – especially when it’s fresh. Is it safe to buy and eat foods from the markets? Most definitely.

In fact, one study by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, showed that South Koreans consumed an average 58.4 kilograms of seafood a year/pp between 2013-2015. This made it the country that eats the most fish in the world, even beating Norway and China.

There are fishtanks outside many seafood restaurants and in major shopping centres like Emart, Kim’s Club or Homeplus, so you can pick your own fish and see how fresh they are.

There are plenty of seafood dishes that deserve mention in this article and for fun, we’ll begin with the most notorious – sannakji. This was the first meal that I had after arriving in Seoul and really cemented my culture shock. It is basically a live octopus brought out to the table and chopped into bits.

Due to the nerve activity in the octopus’ tentacles, they don’t stop moving after death and wiggle around on the plate while you try to scoop them up with your chopsticks. After being sprinkled with sesame oil and toasted sesame seeds, you wrap the sucking tentacles into a leaf and throw it into your mouth.

Beware that due to the tentacles that are still moving and sucking, you will need to chew quite a bit before swallowing as they can be the cause of a chocking hazard.

Moving onto more familiar territory you can also get nakji (octopus) in various other forms from jeongol (broth) to bokkeum (fried). There is also jukkumi, another species of octopus which is usually eaten stir-fried with gochujang and has thicker tentacles.

Saengseon-gui is most probably the most accessible for the Western palate and is just a grilled piece of fish that is lightly salted. It’s usually served as part of a baekban meal (translating to “100 side dishes”, but usually a feast of at least 10 different dishes). It could also come with crab, which is another top Korean seafood dish.

Crab comes in all shapes, sizes and cooking methods. Smaller fermented crab is a popular side dish, while the giant snow crab is notoriously delicious.

And if you’ve ever wanted to explore the vast depths of the ocean in a bowl try haemul jongol or haemultang. Haemul basically refers to a dish of assorted seafood and could mean fish, prawns, shrimp, squid, octopus, crab, clams of various sizes, fish roe, crustaceans and weird and wacky creatures of the depths from sea cucumbers (called haesum or ginseng of the ocean) to the bitter sea pineapple (monggae) to the chewy abalone.

Eating seafood in Korea is a great experience as they truly are one of a kind dishes you will find nowhere else in the world. But it is also more for the adventurous palate and is not everyone’s cup of tea.

Jokbal (pork trotter) & bosam (wrapped pork belly)

Two very popular pork dishes in Korea are Jokbal (pork trotters) and bosam (usually pork belly that is then wrapped in leaves before eaten).

Jokbal is made from cooking pork trotters (a better way to say pig’s feet) in soy sauce and various other spices. The result is a melt-in-your-mouth greasy meat with a spongy skin. They are deboned before being served, but some odds and ends still end up in the meat.

Jokbal is usually served with fermented shrimp sauce or saeujeot, as well as raw peeled garlic, peppers and leaves of some kind as it is usually eaten as ssam (wrapped in lettuce). Be careful as jokbal does come in several intensities of spiciness, the most being “fire jokbal” or buljokbal.

As jokbal is considered anju (food accompanying alcoholic drinks), it’s usually served with soju. While it’s served almost everywhere, the most famous area to get jokbal is around Dongguk University Station in Jangchung-dong, Seoul. Some jokbal restaurants in this area have been open since the 1960s.

As this dish has loads of gelatin, it is rich in collagen and is said to prevent wrinkles and keep the skin nice and firm. Other than this dubious claim, give it a try if you can get past the idea of eating pork trotters, it’s delicious.

Bosam on the other hand is a less greasy pork dish made using boiled pork belly or pork shoulder. Also considered anju, the meal is served with soju, along with plenty of sides like raw garlic, ssamjang (spicy dipping sauce), saeujeot, kkaennip (perilla leaves) and a multitude of leaves.

As the name of the meal suggests (bossam means “wrapped” or “packaged”), you take one of the leaves like napa cabbage in your hand, place the pork in the center along with a dipping sauce of your choice and then any other side dishes over the pork. You then fold or wrap the leaf into a ball and shove it into your mouth.

Top Korean snacks & street food

Between main meals, you can fill up on some delicious Korean snacks. Just pop in to any convenience store and select one of the many options available.

You can also visit any street stall or pojangmacha (small tented street stall) for a wide variety of tasty street foods, which are a meal in themselves. Some of my best meals in Korea were had while standing on the side of the road.

Kimbap (seaweed rice)

Many people refer to kimpab (literally seaweed-rice) as “Korean sushi”, and state that it was introduced during the colonial era. But wrapping food in other food has been a part of Korean dining way before the Japanese invaded and is called “ssam”.

It’s similar to calling kimchi “Korean sauerkraut”. While the exact origin is not known, there are two major differences between sushi and kimbap. The first is that the Korean version is made using sesame oil and is sweeter, while the Japanese variant is made using vinegar and is more bitter.

The second difference is that sushi is mostly made with raw fish, while kimbap has many different fillings from tuna mayonnaise to spam to cheese and even bulgogi!

It’s also one of the easiest snacks to get with eateries making them to go and even convenience stores selling them in easy to open plastic wrappers. The round version is the most common, but the samgak kimbap (triangle kimbap) is also delicious for a quick energy booster and contains more rice.

Odeng/eomuk tang (fish cake soup)

While walking along the streets of Seoul, it’s not difficult to come across two of the most popular Korean street foods that are wheeled around on carts – odeng and tteokbokki.

Odeng, a word borrowed from the Japanese oden, is a synonym for the Korean word eomuk and translates as fish cakes. The processed fish cakes made from ground white fish, potato starch, sugar and vegetables isn’t the healthiest food, but during the freezing winter, it is the best to keep warm.

The eomuk comes either in a long flattened slice on a skewer or in small round balls and is served with a sweet and spicy broth. It’s great to stand on the side of the road, cupping the hot paper cup while watching the snow fall. And even better, it’s super cheap.

Tteokbokki (spicy rice cakes)

The next most popular street food in Korea is the spicy, sweet and chewy tteokbokki, sometimes written as tteokbokki for some reason that is beyond me.

The Korean food is as unhealthy as it is delicious and is made with rice cake tubes (tteok), eomuk boiled eggs, scallions and a sauce made from gochujang, sugar and gukmul (soup broth).

There are all different varieties of tteokbokki from the soup version to stir fried to even curry, jajang (black bean) and soy sauce. The fried ones have quite a nice texture as the outer layer of the otherwise chewy tteok is crunchy. This version usually comes on a skewer and is also called gireum tteokbokki (oil tteok-bokki).

Legend has it that in the 1950s Ma Bok Lim was opening a Chinese restaurant in Sindang-dong and accidentally dropped the cooked tteok in the gochujang sauce and found it delicious. Today the area is also known as Sindang-dong Tteokbokki Town where there are numerous restaurants that offer all varieties, even pizza tteokbokki that has stringy cheese added!

A side that usually comes with tteokbokki is twigim (fritters) which are a variety of deep fried items like prawn, mushroom or pumpkin. Sundae (or blood sausage, pronounced soon deh), is also usually served alongside tteokbokki.

Jeon & Buchimgae (Korean pancake)

Jeon and buchimgae are both Korean-style pancakes made by pan-frying a wheat flour and egg batter in oil with the addition of other ingredients.

The main difference between the two pancakes is the cooking method. With buchimgae, all ingredients are mixed into a single batter and then thrown onto the pan. Jeon on the other hand is more strategic.

The batter is first placed on the pan, then the ingredients are positioned on the batter. More batter is then added to make the ingredients stick. The most common of the jeon is pajeon or spring onion pancake where long strips of spring onion are placed on the jeon.

Other varieties are haemuljeon (seafood), kimchijeon, bindaetteok (made with mung beans), and hobakjeon (pumkin). A small amount of soy sauce is used for dipping. Good luck trying to rip apart the delicious pancake with your chopsticks, it takes some practice. The best alcohol for jeon and buchimgae is makgeolli (sweet rice wine).

Pro tip: “cut” the jeon with the chopsticks. First put one chopstick in each hand. Use the one to hold the jeon and the other to slice. Once it is cut into pieces, eat away. Once you are skilled enough, you can use one hand to slice the jeon with chopsticks. Your Korean friends will be very impressed with your skills.

Sundae (blood sausage)

Pronounced soon-deh, this chewy steamed Korean snack sounds worse than it tastes. Also known as “blood sausage” (see, sounds hardcore) it’s made with a mixture of boiled sweet rice, oxen or pig’s blood, potato noodles, mung bean sprouts, green onion and garlic stuffed in a natural casing.

On the side, there is usually other, more potent steamed offals like gan (liver) and heopa (lung). The snack is dipped into a salt and black pepper mixture in Seoul with other provinces using their own unique dip like soy sauce in Jeju.

Sundae is usually eaten along with tteokbokki and twigim and can be dipped in to the tteokbokki sauce. Another popular variant is sundae-guk which is an off-white broth that has sundae and the offals with spring onion and perilla seed powder sprinkled on top. How is that for an interesting Korean food?

Hotteok & Hoppang (crunchy pancake & sweet bread)

While both hotteok and hoppang are desserts, they are also Korean street foods and have therefore been included here rather than in the next section.

Hotteok is a chewy or crunchy pancake where instead of putting the syrup on the outside, it is enclosed on the inside of the sweet bread. The ingredients of the filling include brown sugar, honey, chopped peanuts or cinnamon that melt together to form a delicious treat.

Hotteok can either be crunchy and airy inside or of the thicker kind, which is usually chewier and more filling.

Hoppang (which is a form of jjinppang, or steamed bread) on the other hand is a steamed bun similar to the Chinese bao that is either savory and filled with meat or sweet with a red bean paste as its filling.

A cute story as to the origin of the name for hoppang begins in 1970. Hoppang was a brand name for the ready-to-eat jjinppang developed by Samlip, a food company. Instead of calling it jjinppang, they used an onomatopoeia for blowing on hot bread, which in Korean is “ho, ho”. They then added ppang or “bread”.

So the name hoppang is actually a brand name, but has become synonymous with, and even taken over the use of, jjinppang. Hoppang is mostly found in convenience stores near the cashier.

Beondegi (silkworm pupae)

This is a snack for the adventurous, although if you didn’t know what it was you’d most probably love his Korean food.

The nutty, tangy bite sized ovals are actually steamed or boiled silkworm pupae. The exterior is crunchy and the inside juicy and it also sometimes comes in a sweeter version with sugar.

It’s more of an older generation snack as it was eaten during the war as a great source of protein. While the best place to taste beondegi is at any market, you can also buy it in cans and eat it at home.

Jwipo (fish jerky)

Jwipo is less of an acquired taste. It’s fish jerky, similar to US beef jerky or Asian bak kwa, but made using a filefish that is dried, flattened and seasoned. Jwipo is chewy, sweet and served hot.

Dalgona (sponge candy)

Dalgona is another Korean dessert street food that is great fun for kids. Translated as sponge candy, it is a sort of caramel flavored crunchy flat snack made from melted sugar and baking soda. When the baking soda is added the melted sugar puffs up and is then pressed.

A picture is added to the centre, usually a flower, heart, animal or rocket. You can then try to eat around the picture without breaking it and it is said that if you can do this you get another dalgona for free. But I’m sure this depends on the vendor.

The process is super fun to watch and trying to eat the candy can turn into a little game to pass some time.

Cup ramyeon (noodles)

A list of Korean dishes without ramyeon is not complete.

Although the instant snack (ramen in Japanese) was invented in Japan by Momofuku Ando (yes, it’s also the name of David Chan’s snack bar in New York), Korea has a massive instant noodle market.

The world over, this is a quick and delicious snack to eat if you don’t have much time or cash and it’s no different in Korea. The major difference between other parts of the world and South Korea is that you can get the snack in an even more convenient form – in a cup.

You just have to walk into any convenience store, pour some hot water in (all stores have hot and cold water available), wait 2 minutes and eat. Grab an egg or some tuna for protein and you’re set for more exploration.

Pro tip: When preparing your instant ramyeon, tear the lid halfway, pour in the contents of the sachets and water and close the lid. To keep the lid from opening, take your unbroken wooden chopsticks and slide them on the lip of the cup’s mouth. Then you don’t have to hold the lid closed or balance something on top of it.

While Shin ramyeon is the most popular and can be found throughout the world, you can get ramyeon in various shapes and forms in Korea. There are thicker noodles like udon, thinner ones like soba and many different tastes from fiery hot to curry to jajang and beyond!

And yes, you can eat your snack right there inside the convenience store. Just remember to clean up after yourself and throw everything away.

Best Korean Desserts and Sweets

While Western desserts are commonly eaten in Korea, traditional Korean desserts are a bit different. Dessert in Korean, and in extension the Far East, are more bean and rice based than the flour heavy Western cakes and pastries.

Read on below to find out which traditional Korean desserts you can try.

Tteok (rice cake)

When a Westerner thinks rice cake, images of a rice cracker usually come up.

In Korea, rice cake or tteok is a chewy glutinous substance that comes out smooth or powdery. There are various types of tteok that differ by method (steamed, pan-fried, pounded, shaped) and toppings.

The most popular dessert tteok are:

- Injeolmi – rectangular in shape and covered with steamed powdered dried beans

- Kkul tteok – with honey inside

- Songpyeon – eaten during the Chuseok holiday with a sweet filling like sesame seeds, honey, sweet red bean paste or chestnut paste

- Mujigae-tteok – also known as rainbow rice cake as it has tteok of different colors

- Chapssaltteok – smooth and thin tteok that resembles Japanese mochi, usually filled with red bean paste

- Yakshik – tteok with chestnuts, pine nuts, jujubes, and raw sugar and soy sauce and steamed for between seven to eight hours

- Sirutteok – the oldest tteok that is made using a “siru” or large earthenware vessel

- Hwajeon – pan-fried in a pancake form with edible petals on top

- Jeolpyeon – thin, plain rice cake that is beautifully cut

Garaetteok (cylinder-shaped rice cakes) is used to make tteokguk and tteokbokki. There are even more kinds of tteok if you can believe it. It’s a great gift to bring for someone from an older generation. Get several kinds from a tteok store and deliver it in a nice bag, they will be very happy to receive it.

Bingsu (shaved ice)

Bingsu is the name used for shaved ice, but many people use patbingsu as an umbrella term, even though pat is the sweet red beans that only go on some versions of the delicious treat.

The dish is made with shaved ice and then topped with any number of delicious treats from fruits of all kinds to ice cream to red bean paste. Some bingsu also has tiny squares of tteok to add to the texture.

There’s a milky version, a green tea version, one with cheese and another with yogurt. Your choices are basically the same as when you visit a froyo store, but better.

Pro tip: Visit Samchong-dong just above Insadong and next to Gyeongbokgung Palace where there are a multitude of bingsu cafes that also serve waffles and gelato. The vibe is trendy, relaxed, romantic and bohemian, even though it’s right next to the Blue House (the President’s House).

Bungeoppang (sweet carp-bread)

Similar to the Japanese Taiyaki pastry, bungeoppang or carp-bread, gets its name from its shape and not its taste. It is a pastry that is pressed in the shape of a cute little carp that is crispy on the outside and chewy on the inside.

It’s usually filled with red bean paste but can have other fillings like chocolate or cream. The smell is too enticing.

Dasik (snack with tea or coffee)

Dasik is a type of hangwa, which is any snack that is usually accompanied with tea (or more recently, coffee). They are basically cookies made that come in various shapes and flavors. Typical flavors include rice flour, soybeans, chestnuts, black sesame, and pine pollen.

They are made using a Dasikpan, which is a mold shaped with numbers, letters or floral patterns.

Yeot & Kkul-tarae (taffy & honey dragon’s beard)

When walking the long ancient street of Insadong you will surely come across two very unique dessert items. The first is yeot, which can be either liquid or solid, and can come in syrup, taffy or candy form. It’s usually sold in the candy form in Insadong.

This is made of bap or cooked rice and malt barley as a base, and can be either liquid or solid, i.e. either a candy, taffy, or syrup.

Keep walking down the street and you will see some very lively and handsome young men singing and chatting away to customers while making kkul-tarae, a variation of the Chinese dragon’s beard candy.

The honey and maltose mixture is kneaded into dough and then twisted and stretched to form many silky threads that resemble a dragon’s beard. Fillings are then placed inside, usually candied nuts or chocolate.

Yakgwa (medicinal confectionary)

Yakgwa is literally translated to “medicinal confectionary”, but it doesn’t have any medicinal properties. In fact, it is only called “yak” as Koreans of yesteryear considered honey to have medicinal properties and the dessert is made using loads of honey.

The word “gwa” means confection, so you will see many hangwa with the word “gwa” at the end of its name. If you come across a food and the seller doesn’t speak English and the food has “gaw” at the end, it is most likely a dessert.

Yakgwa is a deep fried hangwa made from wheat, honey, cheongju (rice wine), sesame oil, and ginger juice. You will know it is yakwa from its flower shape. It also comes in three size: dae-yakgwa (large), jung-yakgwa (medium), and so-yakgwa (small).

Best Korean beverages

Try to tell a Korean that you want samgyeopsal and makgeolli and they will think you are an extremely odd individual. In South Korea specific beverages, especially alcoholic ones, go hand in hand with specific dishes.

At first it seems odd, but after a while you get the hang of it and understand why this is the case.

For example, the clear soju washes down the very oily remnants of the samgyeopsal. Another one is that jeon (Korean pancake) should be eaten with makgeolli (sweet rice wine). The reason? It’s low in alcohol content (6%). It contains protein and vitamin B and has a sour kick to it.

It’s also said that jeon should be eaten on a rainy day because both flour and makgeolli contain serotonin which heightens emotions and cheers you up on days when you feel down.

Whether this is true or not is up to speculation, but the bottom line is that drinking in Korea is a part of the culture and deeply intertwined with social norms.

Non-alcoholic beverages

Visiting a convenience store in South Korea is super fun as there is so much choice. There are different flavors of cold tea from boricha (barley tea) to nokcha (green tea), oksusu cha (corn tea). There is water made from 24 grains and all the usual energy drinks.

Feeling sick, have a Vita 500 (pronounced bita obaek) which is packed with vitamin C. Have a hangover, reach for some Bacchus.

Whenever I personally arrive in Korea, I go straight to the 7/11 in Incheon airport and buy a banana ooyoo (milk). The milky dooyoo (made from soybeans) is another favorite.

Tea is also a major part of Korean culture and you can enjoy a traditional tea ceremony anywhere in the country. Yet the best way to do it is in Insadong or Bukchon where you can put on a Hanbok and walk around the ancient Hanok houses.

As mentioned in the opening, coffee culture in Korea is next level. There are sometimes five coffee shops next to each other. One thing to understand is that a cafe is a nice meeting place for friends or colleagues or even a place to work or study.

All you need to do is purchase a coffee and you can sit on your seat for however long you want. No one will give you the evil eye or make you feel guilty by constantly asking if you want anything else. Even better you get free Wifi and a charging station. Many of my Korean friends leave their laptops on the table when they go to the toilet, but I have yet to do this.

Alcoholic beverages

As mentioned above, drinking alcohol is deeply embedded into the Korean culture. Before getting into what the drinks are, it will be good to know about Korea’s drinking culture and the etiquette involved.

Drinking culture and etiquette

When working in Korea, you are expected to go to frequent hweshik or a company dinners, where you will need to follow the pace of your boss. Late attendees are also expected to catch up with shots.

The work place in Korea is a very stressful environment where the mood is serious and focused. Drinking loosens that mood and colleagues can have friendlier conversations and discuss personal issues, using innebriation as an excuse to open up. It is still a nice way to bond and create a family atmosphere.

There is also quite a strict etiquette to follow when drinking with colleagues or elders. For example, you will need to constantly be aware of how much alcohol is in the older person’s glass, topping it up whenever it’s empty without them asking.

Unwritten cultural rules state that when you drink with someone older than you, always drink with two hands and look to the left when drinking. This is considered polite. You should also try not to decline when offered alcohol and should drink as much as the oldest person at the table.

Note: While it is legal to drink in public spaces in Korea, please use your discretion and don’t sip a beer in the subway. While this is not illegal, it is bad manners and the people around you will feel uncomfortable.

The most popular alcoholic drinks in South Korea are soju, makgeolli and beer.

Soju (rice wine)

One could say that objectively, soju brand Jinro is the world’s best selling liquor, well before Indin Whiskey brands or Smirnoff Vodka.

Literally translated, soju means “burned liquor” and its origins date back to the Goryeo era during the Mongol invasions when the Levantine distilling technique was introduced. Similar to sake, it is a clear rice wine but has a sweeter taste and is only drank cold.

It has an ABV of around 17-23% but can go up to 53% for the higher range Hwayo brand. There are three major soju brands in Korea and each Korean has their favorite. Jinro, as mentioned above, is the world’s top selling alcohol.

The other two Chum Churum and Good Day (locally known as Joeun Day) are also popular, particularly in the south.

Soju is usually sipped from shot glasses and downed in shots, but the Koreans have also created various soju bombs and the popular somek (a combination of soju and mekju (beer)). Recently, fruit soju has gained popularity with all kinds of flavors, making it sweeter and more palatable. I still prefer to mix orange juice with soju which we used to call sojuice.

It’s interesting to note that Koreans have divided their alcohol into takju or “opaque wine” and cheongju or “clear wine”. Soju is the latter, makgeolli is the former.

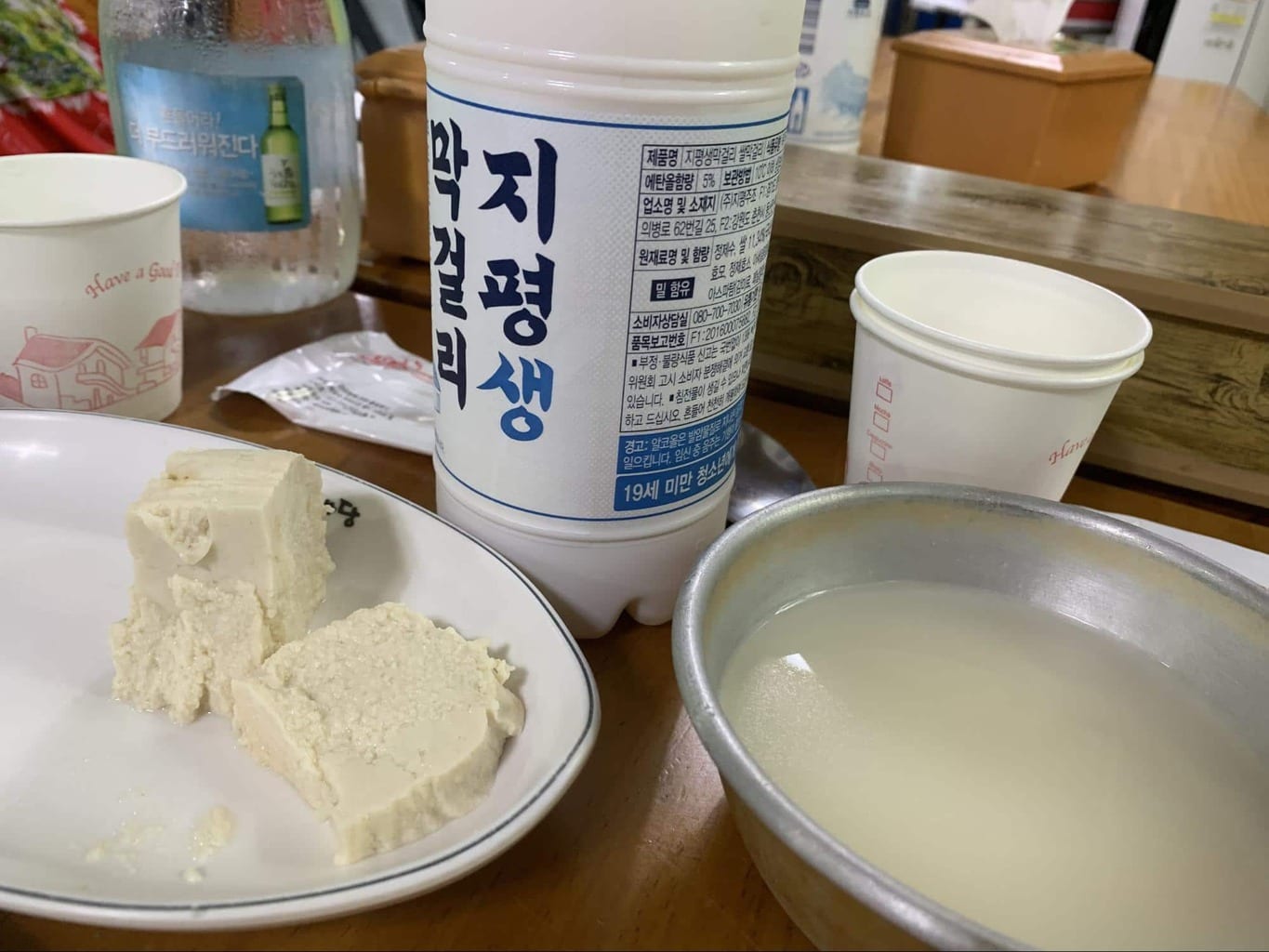

Makgeolli (sweet rice wine)

Beware, makgeolli is delicious and you will drink it like juice but it gives you a legendary headache the morning after. And worse of all, it is ridiculously cheap. Sip it with caution, lest you want to feel like a truck hit you when you wake up.

Before soju came in, was the oldest alcoholic beverage in Korea, makgeolli. Brewing rice wine goes way back to the Three Kingdoms period (18 BC-660 AD). The main fermentation starter in makgeolli is nuruk made from wheat, rice or barley.

Makgeolli is so embedded in Korean culture that there have even been songs written about it, like the one above from Busker Busker where he refers to the thick rice wine as “Ivory Magic”. The Scottish band Colonel Mustard & The Dijon 5 called it “Fight Milk”.

This thick, viscous, milky, sweet, tangy, bitter, cloudy rice wine is a low ABV alcoholic drink of about 6-9%. As the sediment falls to the bottom of the bottle, it needs to be shaken before being poured into the drinking bowl. This gives it a slight fizziness.

Makgeolli is best sipped fresh (about a week after production) and actually has a very brief shelf life. Some imported makgeolli undergoes further pasteurization to enhance its shelf life, but this cuts many of the complex enzymes and robs it of its flavors. Leave it too long and you’ll have rice vinegar.

As jeon (Korean pancake) is the best accompaniment to makgeolli, you will find plenty of makegolli-jips (“houses”) around the country, particularly in university areas. Here, makgeolli is served in a large bowl with a ladle. You then scoop the liquid into your smaller drinking bowl and sip it after swirling the sediment around.

This is a different drinking process than soju, as it is sipped instead of going bottoms up. In restaurants it’s served in a plastic bottle. Before drinking, turn the bottle upside down and give it a shake. Turn it back around and use your thumbs to “pop” the bottle at the bottom of the neck. Do this about 4 times and the fizz will lessen.

If you open after shaking, like sparkling wine, it will go everywhere. If you’re not sure how to “pop”, then just open it slowly and incrementally and let the fizz escape before serving.

Beer

Beer, or mekju, completes the triad of top Korean alcoholic beverages. The top three most popular beers in Korea are Cass, Hite and OB Lager (Oriental Breweries). They are quite mild and can taste slightly watered down.

Beer’s history in Korea is rather new with the first brewery opening up in 1908 and some of the top breweries that still exist today opening around the 1920s. After some very strict regulations were lifted back in 2011, microbreweries started popping up around Seoul.

Itaewon and Haebangchon (known locally as HBC), in Yongsan-gu where the US military base is located, is the center of the microbrewery boom.

Today, there are several great smaller breweries that make some very exciting brews. The Booth and Magpie are the most well-known and should be visited if you’re a fan of beer.

Other alcoholic beverages

Although soju, makgeolli and beer are the most popular alcoholic beverages in Korea, there are many others to try. Insamju and baekseju, for example, are medicinal wines made using ginseng among other ingredients.

There is wine made from persimmons which you can sip in the wine tunnel of Cheongdo, just south of Daegu, that is a restored railroad tunnel built in 1898.

Another favorite is bokbunja, made with Korean black raspberries, and is a very sweet and fruity alternative.

- Check if you need a visa, get help processing it at iVisa.

- Never ever leave without travel insurance. Get affordable coverage from World Nomads or long term insurance from Safety Wing.

- I find all of my flights on KAYAK. Check their Deals section too.

- Search for all your transportation between destinations on the trusted travel booking platform Bookaway.

- I book all my day trips and tours via GetYourGuide, they are the best and their tours are refundable up to 24h in advance.

- Get USD35 off your first booking with Airbnb.

- Compare hotels EVERYWHERE at HotelsCombined and book with Booking.com.

- Compare car rental prices at Rentalcars.com