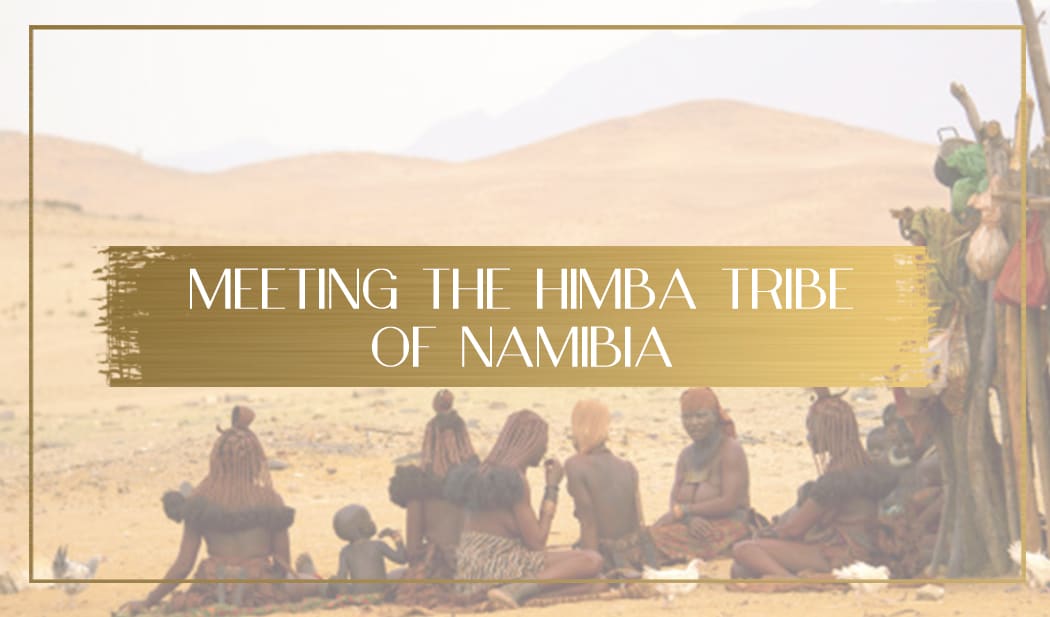

Fascinating images of the Himba, one of the last remaining nomadic tribes of Africa on the pages of glossy travel magazines cannot even begin to explain the incredible feeling one gets interacting with them in skin and bone.

A brief history of the Himba

There are only about 50,000 OvaHimba left in Namibia although census and accurate numbers are hard to obtain, as they inhabit a mostly remote and inaccessible part of the world. The Himba are semi-nomadic pastoral people and constantly re-build and abandon their villages in search of greener pastures. They are descendants of the Herero and originated from East Africa. It is believed that, in the 16th century, the Herero crossed the border into Angola. When severe droughts threatened to kill all of their cattle in the 9th century, some of the Herero decided to stay and find other means of survival whereas a large group continued down into Namibia’s Kaokoland region and tried to start afresh. The word Himba means beggar in Otjiherero language. This is because, when they moved into Namibia, cattle-less, they had to beg and ask for cows and goats from other tribes.

The Himba are cattle herders and live of the land. The most unbelievable part is not the fact they are pastoral and hunter-gatherers in today’s developed society, but that they live in some of the most inhospitable and arid parts of the world where survival is a constant challenge. Many of them, at least the ones we interacted with, understand and have been exposed to modern life, yet choose to stay away from it. For how long? Hard to tell, I found out, spending two evenings with two groups in the Northern part of Namibia.

Expectations before meeting the Himba people

My perfect trip to Namibia had to include the Sossusvlei dunes, the Skeleton Coast and a visit to the Himba people. Although the first two items on my wish list were relatively easy to organize, a visit to the Himba is extremely difficult because they are largely located in a part of Nambia that is off-limits to tourists and for which GPS coordinates don’t even exist. The North of Nambia, especially the Western part of it, cannot be reached following GPS coordinates. A quick check on Google Maps indicated that the large area expanding 14,000 square kilometers had not been mapped. “Occasionally, South African explorers who venture out off-road into this part of the world, document GPS coordinates and then swap them”, with fellow 21st century Livingstone lookalikes, that is, confesses the General Manager of Serra Cafema Lodge, where I am staying on my visit to the Himba. It takes the caravan bringing supplies to the lodge from Windhoek two days to drive the 800 kilometers distance. Roads do not exist and the journey is done through dirt and gravel tracks or by simply driving through the desert dunes. It is an arduous job and one that is rewarded with the most incredible landscapes. In Namibia, the journey is the destination.

Before meeting the Himba, I was not sure how much of their looks and behaviors were genuine and how much had been adjusted to perpetuate the image for tourists. After having spent two evenings with them I am positive that their ways of life are the same they were hundreds of years ago with some help from today’s modern society. “If the lodge was to disappear all of a sudden the Himba would not even notice”, assures Dawid to the group of five other tourists and me who are standing at the edge of the Himba village on the 3rd of January. After chatting about life, relationships, culture and traditions with them for four hours over two evenings, I believed him.

Coming face to face with a group who still lives prehistorically is almost impossible today. The concept of a pastoral or hunter-gathering society is lost in the definitions of a book. In real life terms, that means that the men are out with the cattle for extended periods of time constantly on the move, looking for green pastures to feed the sheep and goats. In the desert, this may be extremely tough as rains are scarce and the vegetation is simple. For the women, time is spent in the semi-nomadic village with the children and the rest of the women. They cook, gather fruits, cereals, roots and berries from the nearby area, wood to make fire and water to drink. In Namibia, and for the Himba, this has an added layer of difficulty as the terrain is dry and devoid of much life and the sun is forever beating their dark ocher-covered skin.

What made the Himba extra fascinating to me was their ornaments, outfits and red ocher with which the women cover their entire bodies. I had erroneously assumed and read in many articles that the red paste was used to protect from the sun or the insects, just like some Asian countries use a yellow mixture to protect the skin and keep it whiter, but the Himba told us that they use this mixture of animal fat and red powder as a beauty product and constantly apply it to body and hair to look beautiful. Proof of that is that the men do not apply the paste. Their slender and tall body is covered with jewelry and ornaments. They have long dreadlocks which end in tassels and are plastered with ochre. Above the braids and on top of the head, a married woman will wear a piece of goatskin called Erembe and shaped like two palms cupped together. Also covered in the red paste, the piece is attached to the hair with a string and decorated with beads and pretty colors.

Wrists and ankles are decorated with trinkets, bracelets and ornaments made from beads, iron, plastic, copper and wire. Some of them can be very heavy. Aside from being an accessory, the ankle bracelets are also used to protect from spider bites. The most fascinating piece is the calfskin skirt that hangs from their waist over the backside. A collection of strings tightened at the front holds pieces of calfskin tainted with the same red mixture and looking like a flamenco dancer’s ruffle. They must be heavy, for the calfskin is thick and looks like cured leather, and forces them to always sit leaning forward. It is beautiful in its own primitive way. The Himba women are practically naked except for the ornaments and the skirt. They wear a piece a cloth covering their front and their breasts are in the open. Children wear a loincloth too. At night, when the chilly desert becomes freezing, they use goatskins or blankets for cover. These blankets, much like the ones I could use anywhere else, are one of few nudges to the modern times. As are some of the plastic bags used to hold belongings away from the floor.

Socially, the Himba follow a tribal clan structure and each of them belongs to two clans: the mother’s and the father’s. Each village accommodates one large family. During our visits to the two villages, there were numerous relatives visiting. This structure is believed to help with survival in such hard territory as it gives them two sources of help in case of need. They are also animists and believe in one sole God and in the power and importance of ancestors. A constant fire symbolizing the ancestors is constantly burning. Modern medicine is not used, instead, they have witch doctors that can be called upon should there be a need.

What it is like to visit the Himba

The Himba we visited were in good terms with Serra Cafema and, especially, with our guide Dawid, who spoke their language. Being also a descendant of the Herero, his mother tongue was similar to that of the Himba and, since he started working with Serra Cafema and interacting with them almost daily, he became a master in their language. As soon as we arrived in their camp, only 20min from the lodge, we were welcomed with a smile. Dawid taught us how to say hello and introduce ourselves. He advised we should first greet them, then introduce ourselves one by one before we could take their photos and ask questions, which he would help translate. We could have a normal conversation, the Himba were friendly and open to discussing day to day topics. And they were remarkably savvy and aware of the modern world, even if they had decided to carry on with their traditions.

As we said our names, the Himba women repeated them, laughing and commenting after a few. I asked their names too and we tried to repeat them as well. Formalities were then out of the way and we could get down to photos and conversation. They were friendly and, despite the language barrier, one could tell that humanity speaks only the language of respect and openness. Through gestures and facial expressions we could converse. Dawid translated where the universal sign language did not reach.

Although they have interacted with civilization all too often and they regularly go to the lodge to buy some basic items, the Himba have decided to remain in their essential lifestyle. They cook basic foods, sometimes made of maize porridge for days on end, they look for berries in the desert and collect water from the nearby river. But do not live too close to it, for there are crocodiles that could eat their livestock, their chicken or their children. Their houses are plastered with cow dung but, when we arrived, the draught that had hit Namibia before our visit, had caused them to rely on blankets instead for there wasn’t enough water to cover all the huts. Children and chicken were grazing and playing around and the babies were breastfeeding from their mothers, their mouths also covered in the red ocher, their mother’s breasts hanging down looking like a pair of cow udder. The Himba don’t place any sexual attachment to a pair of breasts. An inquisitive child wanted to play with me and placed his hands on my thigh, leaving a red mark on my white skin. “Be careful, it is really hard to wash off”, had warned Dawid on the way to the camp to those of us who were thinking of shaking hands with the Himba. He was right indeed and two days later I was still able to see the child’s hands on my thigh, a mark of the remarkable evening with his family.

Mesmerized with the visit and curious to hear more we arranged another visit to the other village across the sand dunes for the day after. The Himba in that village were a smaller group and had exactly the same traditions and customs, as expected, but they were even more inquisitive and less shy. Here, a deep human exchange took place. As I placed the camera down and started recording I found myself answering questions related to why I was sharing a room with a friend, and hearing explanations from the two other visitors traveling with us about why they had no children. Social rules and convention had determined that friends should not sleep in the same room and that couples should have children. The Himba start having children as soon as they are physically able and, using no contraception, that may mean having several children. “The population is increasing”, told us Dawid, for they have as many children as nature wants to give them.

In the second village, we realized that one of the girls was dressed in modern clothes, wearing a pair of pants, a colorful tshirt, sandals and even hair extensions. We were surprised and asked what their views were. The women quickly answered that in today world, they can no longer force anyone to follow their traditions. Modernization and interaction with the rest of the Namibians had brought them major advancements. Since the Himba ideal of beauty does not comply with the way she was dressed, they viewed this as a challenge. The girl had got the clothes from tourists and the extensions from a girl at the logde who was selling them.

Suddenly, half way through our conversations, one of the kids arrived, fully clothed in a western outfit and speaking English. He was a Himba too, but was attending the local school where he was taught how to write and read and how to speak English. As education becomes more pervasive, so does the risk of disappearance of the Himba culture. But this process may take decades as their semi-nomadic lives do not help with schooling and the traditions usually prevail.

After a couple of hours interacting with them, asking questions, observing, inquiring and answering their questions we were ready to have a look at their handicrafts. We had been told to bring some small change to buy some of the souvenirs, bracelets and handicrafts the Himba women make as a sign of appreciation. It seemed only fair that they would open their houses and their lives to us and we would show them our gratitude with a pretty item we could take home. Each of the women and the children laid out their wares on a blanket in a circle and we went around having a look. I bought three bracelets for $20. This money would be used to purchase food from the Lodge’s small shop.

As the sun was setting behind the desert dunes I was sure that the Himba village was not a staged tourist attraction. They were incredibly friendly and as curious about our life as we were about their. It was their reluctance and stubbornness to continue with their old traditions that struck me the most. As we drove passed their village several times during our stay, I saw them going about their day. The children were playing, and the women were tending to their homes and making food. Life went on in the heat and dryness of the desert.

As we were driving to the airstrip on our last morning, we saw the cattle had returned and found the men and women sitting around a fire exchanging the stories of the previous months away. As the Himba are polygamous, the five women were met with only two men.