After almost 6,5h game driving and sand bashing in the ever-changing Namibian landscapes a triangle of dark blue ocean appeared between two sand dunes. We had finally reached the Atlantic Ocean coast on our Skeleton Coast trip.

History of the Skeleton Coast

The Skeleton Coast Park extends from the Ugab River to the Kunene River, which marks the border with Angola, on a narrow 50km stretch of land along the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Namib-Skeleton Coast Park, the sixth largest protected area in the world, covering over 16,000 square kilometers, and the largest park in Africa.

As Amy Schoeman, wife of Louw Schoeman, the pioneer in eco-tourism in the Skeleton Coast, put it in her Skeleton Coast book, “The remoteness and untouched nature of the terrain has therapeutic and perspective-giving qualities”.

After 4 days without internet or any contact with technology or the outside world and an overdose of these mind-numbing landscapes, I could not agree more.

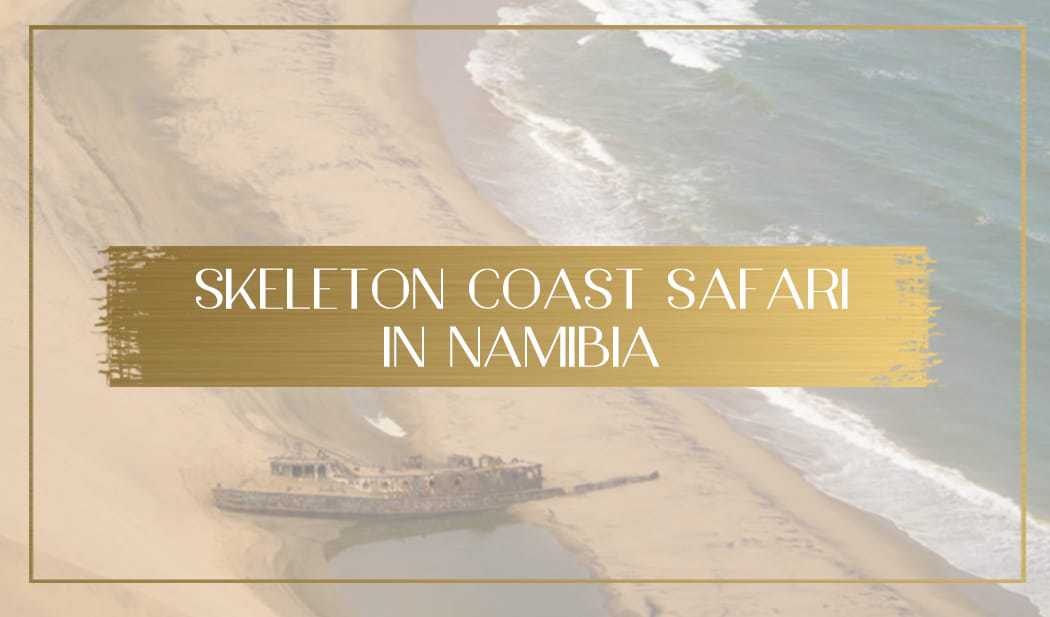

The name Skeleton Coast is synonymous with the many bones of ships, whales and humans scattered along the coastline. It is one of the most inhospitable and deserted places on Earth and one with the highest concentration of shipwrecks. Stranded seafaring men would think they were safe, before the desolate sand dunes would send them to a sure death.

The park was created in 1971 as a wilderness area, that is, an area where development and tourism are kept to a bare minimum and whose access is limited.

Since 2004, the Skeleton Coast fly-in safari concession is held by Wilderness Safaris, with whom I was traveling, and nobody else can take tourists to the park with the exception of Skeleton Coast Fly-in Safaris, on a gentlemen’s agreement with Wilderness, the Serra Cafema’s Manager tells us.

Namibia Tracks and Trails guides twelve tours a year into the area. No other company or the public can access the large and incredibly remote area Southwest of the Kunene River. The Southern part of the park, closer to Swakopmund, Namibia’s second largest city, is accessible to day visitors and overnighters at basic camp sites but the majority of the park is exclusively accessed by fly-in safaris.

In 4 days we did not see any other car or visitor and the many signs indicating the private access to Wilderness’ concession were common. Most people visiting the Skeleton Coast either stay in the Southern part or fly over it, observing its surreal magic from a bird’s eye view.

I had the privilege of driving through it, on it and then fly back to the lodge over the coast in what was an incredibly special day. Only 800 people get to visit this part of the world every year and, on my trip, most of the other guests were repeat customers.

Despite the landscapes look inhospitable, barren and inhabitable, it can take up to 100 years for the bruises left by car tires on the harder layers of the desert to disappear. Wilderness Safaris guides follow pre-determined tracks that were created following careful thinking and planning and never deviate from this path. Behind the tough look of the landscapes lies an incredibly delicate eco-system or desert-adapted wildlife and plants.

The Namibian Government is serious about conservation and the country is the only one to have included conservation in its constitution. They are not joking when they limit the amount of visitors to the protected Skeleton Coast Park to Wilderness Safaris Hoanib Camp which has less than 18 guests at any given time. If the availability wasn’t enough to deter demand, prices at Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp start $1,300 per night.

The landscapes here, as in the rest of Namibia, were spectacular. Jurassic age lava covered the Namib Desert some 150 million years ago. This lava is what can be seen today when flying over the Skeleton Coast and it is truly mesmerizing. They are also the reason why Namibia’s mining value is so impressive.

Bushmen called the Skeleton Coast “The Land God Made in Anger”, and Portuguese sailors who first discovered it referred to it as “The Gates of Hell”. Both illustrate the area’s reputation and its magical powers.

The rugged beauty of the Skeleton Coast

Before I visited, the Skeleton Coast was a sea of pale sand dunes meeting the violent ocean in an all-enveloping and mysterious fog cover. On most days, the coast can only be seen below a layer of impenetrable mist, the reason why so many ships missed their journey and ended up stranded on the sand or hitting a rock.

This fog is also the source of precious moist and water that guarantees survival in the arid desert. Desert-adapted animals and plants look for this moist as their only source of water in an area that receives less than 3cm of rainfall a year. They have learned to live without any water in what seems like a mammoth feat.

To my surprise, and on another unexpected day in Namibia, when the car reached the shore, the sun was shinning and the weather was warm, only cooled down by the icy Atlantic wind that makes this area so unique. The fog dissipates only on 25 days out of the 365 days in a year. On the remaining 340 days, it covers it all. We were incredibly privileged to see this part of the world in all its clear splendor.

Tales of sunken ships, like the famous Dunedin Star, rescued fugitives, recovered bounties and tales of explorers vanished under the clear skies are all associated with the Skeleton Coast. The bright sun and blue skies made it look all the less daunting.

Two days earlier, as I was flying out of Swakopmund, Namibia’s second largest city, I spotted abundant car tracks along the sandy beach. The Skeleton Coast starts north of Swakopmund. At Mowe Bay, where we headed, the sand was undisturbed, shifted only by a single car track and the ever-blowing wind.

The sand dunes were towering high, and falling sharply on the edges. The wind was blowing the top layer, softening the waves. It was mind-blowing to realize that, on a stretch of land that could go on for 500km, there were no other human beings than us four.

The feeling was not that of solitude, but of reflection and peace, despite the parched landscapes and the strong waves beating the shore.

We started the day driving along the dry Hoanib riverbed stopping for springbok, desert-adapted giraffe and elephant, oryx, birds of all types, a brown hyena and jackals. We traversed bone-dry sandy areas with only ana trees, endemic to Namibia, bushes and acacia.

We climbed dunes built between flat-topped mountains. We passed large grey granite outcrops, eroded by the wind, sparkling mica schist rocks and fields of white quartz. We crossed flood plains, where tall grasses had grown fed by the summer rains.

Below the greenery, animals were hiding. In some parts, the sandy path was flanked by overgrown thorny bushes that had created a tunnel as high as our purpose-built Land Cruiser. I held on to the roof bars when the top of the vehicle was open and felt the dry and exhilarating air of the desert on my face.

Amid the barren desert and the ever-changing landscapes there were real oasis. Elephants can go for three days without water until they find a waterhole. “Nature is wise”, I thought to myself. So are humans, I would later find out as we spent two evenings with the ancient Himba Tribe in the north of Namibia.

With skill, intelligence and observation even the most vulnerable of creatures had found a way to survive the lack of water and visible food.

“They have very long roots that can go as far down as 40 meters”, expertly pointed out our guide, Liberty, “even if the riverbed appears dry, there are subterranean flowing waters”, he continued as we wondered how the trees could be so green if there was no water to be found in hundreds of miles.

This was a reasoning that we had heard before, in the Namibrand Reserve. Namibia has ben the center of multiple documentaries on animal’s ability to adapt to the most impossible of conditions.

As soon as we spotted the ocean, the vegetation and the rocky mountains disappeared and all we could see was the sea of sand waves that the Skeleton Coast is known for.

Some were topped with reddish mineral deposits, others with black sediment, this was not the usual blond desert of the Arabian Peninsula or the Sahara, the Skeleton Coast was a tide of changing colors meeting a battling sea. The real-life views looked like a painting.

Before we reached the shore, we climbed on top of the highest dune and parked the car at the very edge of the dune. Below, there was only an eroded and steep sandy wall. We soon drove down that edge in what appeared to be a feat only someone who had lost his judgment would embark on. “Welcome to the land of the brave”, repeated Liberty again, as we descended down the dunes.

It was not just bravery that was required to venture down the highest and steepest of dunes, but also a sense that impossible is nothing. Namibia sure felt, all along, as if nothing was impossible and, with enough preparation and determination one could conquer the world.

We tumbled over the edge on what looked like a 90-degree incline but he soon killed the engine and the weight of the car, plus the five passengers in it, sank the vehicle deep into the dune almost to the wheel level and we slowly slid down on a 33-degree ride as the sand roared with us.

It sure had my heart spinning for the first few seconds when I was standing perpendicular to the car’s floor, at the edge of the dune. After the trick to impress the tourists was over, we drove the last few meters towards the shore at Mowe Bay.

The seal colony at Mowe Bay along the Skeleton Coast

Approaching Mowe Bay, a vomit-inducing stench of death and excrements filled my lungs. As the smell became stronger and harder to ignore, it became apparent that we had reached a 30,000 seal colony populated almost entirely by hundreds of months old cubs who cried and called for their mothers non-stop. It was as if nature was showing us all its almighty power.

I had wrongly assumed their droppings were the cause of the then unbearable smell, but it was instead the result of the rooting carcasses and bodies of the dead cubs who, having lost their mothers in the crowded colony, met their death in the form of starvation.

After walking past a rocky area covered in the decomposing bodies and feeling my stomach churn, I managed to fight a rush to throw up before finally reaching the sea. The Atlantic winds had blown most of the smell away and I was met with a large amount of black tiny seals playing, swimming in the water puddles and calling for their mothers.

Among the loud calls, the fighting of some of the few adults and the fishing and surfing of the grown up seals in the towering waves behind, we enjoyed the playing cubs and I managed to overcome the smell. The theory of natural evolution was right before our eyes.

The weaker ones had perished, their bodies decomposing. The stronger ones were calling for their mothers and showing signs of independence and self-sufficiency. Few adults were fighting over territory, females and food.

The grown-ups were fishing, taking a dive and looking for food in the deep cold waters of the Atlantic. Although the water on the shore was incredibly chilly, usually between 12 and 15 degrees, the Benguela current is responsible for warmer waters inside, with temperatures reaching up to 18 degrees further in.

Our journey continued with a visit to the local museum by the park station. The entrance to the park is flanked by two skulls and the sign of death. The Skeleton Coast’s reputation was obvious in the map illustrating every shipwreck, some as recent as the 1970s, despite being equipped with all the modern navigation tools.

One of the most famous ones, the Dunedin Star, is said to have taken down two additional ships that came to its rescue with it. Inside the small tarpaulin structure there were bones and skulls of various animals including the baleen of a whale, and a human skull, whatever had been found and rescued from the strong sea.

The Shipwrecks of the Skeleton Coast

After the seals and the museum we were ready to explore one of the many shipwrecks that were nearby while Liberty prepared lunch on a quiet spot on the beach with the waves beating the coast and the overgrown seaweed swinging back and forth with the water.

The surf was so strong that, in the times of human-powered boats, boats could land on the sand but they could not launch from it. After observing the power of nature and the sea and the advanced state of decomposition of a ship that got stranded only forty years prior, we sat down on our comfortable safari foldable chairs to a lunch of wine, salad, pasta, chicken and meatballs.

Life was good on a sunny day in the solitude of the Skeleton Coast park. It was incredible to know that, for the next hundreds of kilometers, nobody else was standing on this very sand.

Our return to Hoanib Skeleton Coast Lodge, where I was staying, was no less special. The drive to the coast was adventurous and dramatic, but driving back through the bone-breaking dunes and mountains again would have been hard on the body so we flew back on a 20min scenic flight that gave us views over the seal colonies, the flamingos and the absolutely breath-taking landscapes of the Skeleton Coast park. Another once in a lifetime day in Namibia.